I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Munch's 'Scream'.

Did Edvard Munch predict the future?

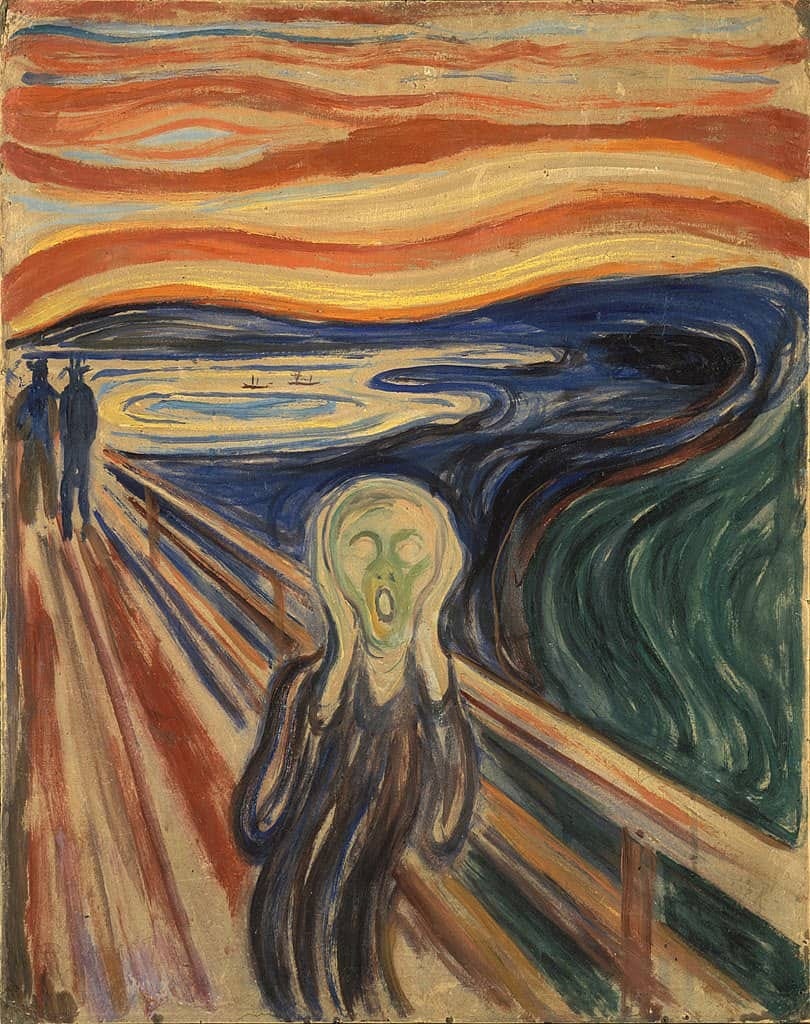

‘The Scream’ is one of the most famous paintings in art history.

It’s been stolen twice, mimicked in popular horror films, and even helped shape the design of the shock emoji — 😱.

But what if I told you that in today’s world, The Scream is more relevant than it’s ever been? With some even calling it “the ultimate image for our political age”.

Under a fiery sky of red and orange swirls, a lone figure stands on a bridge. Behind him, the sea twists and turns, merging with the blazing sunset above. But the man seems oblivious—lost in a moment of shock, terror, and panic. Wearing a navy robe, he holds his arms to his skull-like face and looks to us for help. His hollow eyes widen to form gaping holes and his mouth stretches open; frozen in a blood-curdling scream.

On the 22nd January, 1892, Edvard Munch recorded the exact moment of inspiration for this work, writing:

“I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun went down – I felt a gust of melancholy and suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing…my friends went on – I stood there trembling with anxiety and I felt a vast infinite scream through nature”.

In the late 19th century, a surge of global discoveries spurred a monumental movement, called Modernism. Suddenly, art, music, architecture, politics, science, even theatre all saw immense transformations. But, the biggest change was to people’s everyday lives.

In towns, urban life began to thrive with a new sense of enthusiasm and excitement. Industrialisation made its way into big cities, influencing streams of mass production. The expansion of railways, telephones, and early automobiles improved connectivity. And the rise of early feminism opened people’s eyes to deep-rooted injustices. For some, this shift brought a new sense of optimism, a feeling of promise, and a premonition of hope to come.

But, for others, feelings of anxiety and fear clouded their thoughts. As science advanced, religion waned, and soon the term ‘existentialism’ forced people into a frenzy about the uncertainty of life’s meaning. With this, a fuelling interest in psychology sparked panic. New, unexplained illnesses like ‘hysteria’ and ‘neurasthenia’ provoked trepidation about how the expanding city and modern life would affect people’s mind. And soon, this link between modernity and anxiety became inseparable for some, including Edvard Munch, who made it the central theme of his art.

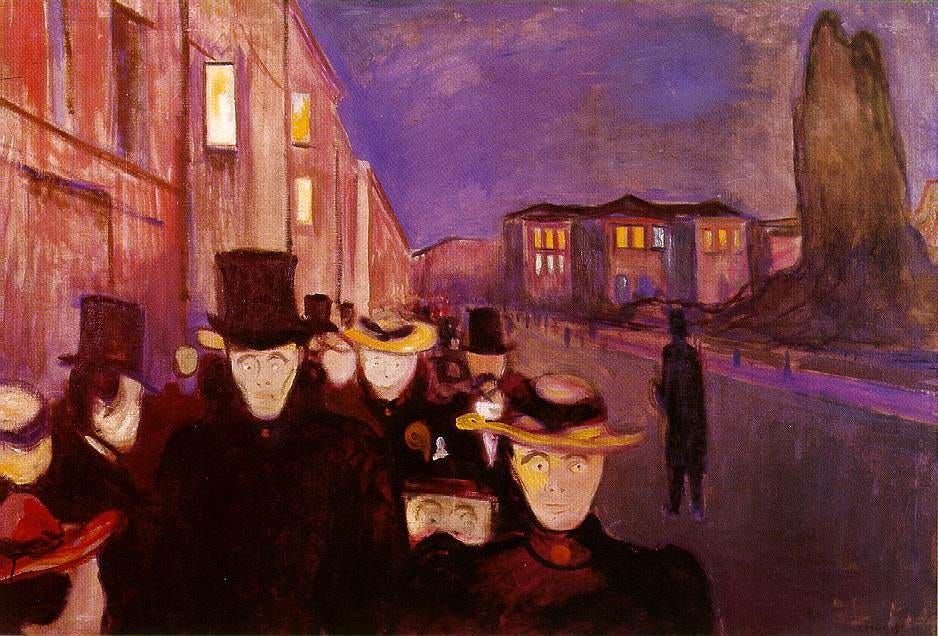

Take this work, for example, entitled ‘Evening on Karl Johan Street’ (1892):

For many today, this painting feels familiar—a snapshot of a bustling street. Yet, like The Scream, it carries an almost apocalyptic tone. Under the dim light of dusk, the busy street is transformed into a place of claustraphobia; its atmosphere thick with unease. The zombie-like crowd stares ahead in a trance, while a solitary figure walks away, isolated and detached. As we watch him retreat from the overstimulating crowd, we can’t help but wonder: Who is he? Where is he going? And, why is he alone? Yet, it’s this exact sense of alienation and isolation that defines Munch’s work.

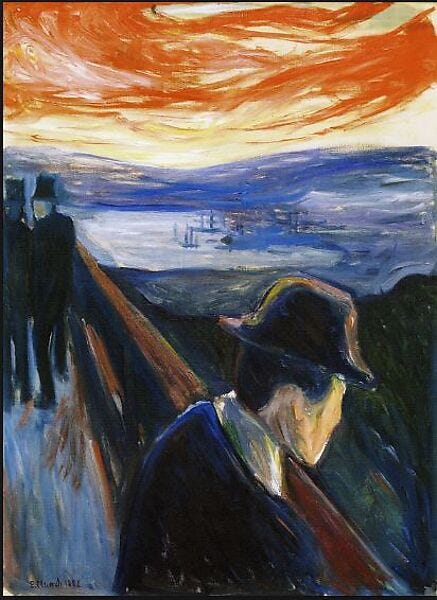

‘Sick Mood at Sunset, Despair’ depicts a similar scene—almost a mirror image of The Scream.

Rooted in Munch’s memory of witnessing his sister’s death, this piece captures a moment of deep reflection. Although the figure’s features are blurred, his anguish and helplessness are unmistakable—emotions that many of us have felt.

But how does this all relate to our world today?

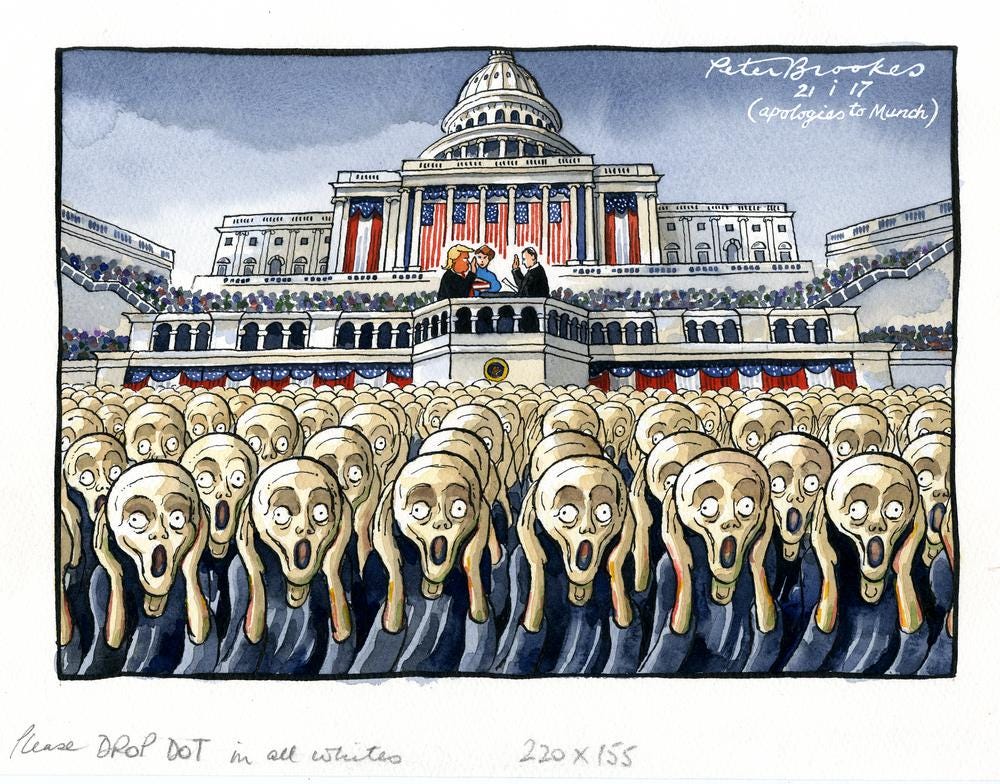

In 2017, cartoonist, Peter Brookes, drew on Munch’s imagery to sum up the widespread anxiety felt by people following Donald Trump’s election as president. In Brooke’s illustration, the crowd at Trump’s inauguration metamorphosize into the well-known screaming figure.

Now, years later, we find ourselves in the exact same predicament with an even greater level of uncertainty and unease.

In today's world, Munch’s work remains as relevant as ever, capturing the anxieties that define our time. Whether you feel like screaming into the abyss, withdrawing from an overwhelming world, or pausing to reflect, his images provide a space for those emotions. By anonymizing his figures, Edvard Munch allows us to see ourselves in their place. His art doesn’t offer an escape—it offers recognition and release. When we feel unable to voice our distress or make sense of our emotions, his raw and haunting images give us a visual reassurance that we are not alone in our struggles.

“My art is grounded in reflections over being different from others. My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings”. — Edvard Munch.

Such a good read! Love the way you contextualised that intense dread and terror Munch captures in his works

https://open.substack.com/pub/clementpaulus